Jeannette Piccard pokes her head out of her Stratospheric Gondola after her record-breaking ascent.

“Dying is the last Great Adventure,” the Rev Dr Jeannette Ridlon Piccard told me as she lay dying with Congestive Heart Failure. The courageous high-altitude balloonist and first woman ordained to the Episcopal priesthood has inspired me for 50 years. Now her mighty soul accompanies mine on the Journey to Infinity.

At her ordination as a deacon in 1971, Jeannette was presented by her granddaughter, Jane, left, then a U student in social work. On the right is Rev. Denzil Carty, first to affirm her calling as a priest. Minneapolis Star.

My Congestive Heart Failure was diagnosed in May and has progressed rapidly from acute to fatal. Blessedly, I am mostly free of pain. Numbness and increased daily as congestion rises from feet and legs toward gut. Breathing is greatly aided by oxygen 24/7.

Even more blessedly, I am physically, emotionally, spiritually and mentally upheld by the most unconditionally loving people on the planet. Plus the caring, compassionate comfort-care from VNA Hospice Team and my wise, kind and seasoned Doctor of Osteopathy. They come into my home daily with healing hands and hearts, so I am richly blessed with unconditionally loving TLC.

I welcome your prayers on this last Great Adventure. It feels great to sense your presence as I navigate the Great Sea of Unknowing into the Heart of God.

Jeannette Piccard tells her ballooning stories to her grandaughter Betsy in 1963

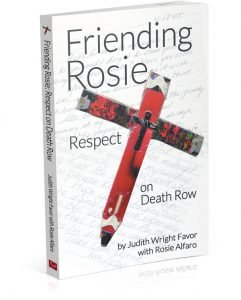

This special event sheds insight on those who are incarcerated and on death row – exploring themes of friendship, compassion, and understanding the realities of a life behind bars. Proceeds from book sales and donations will support the Prison Library Project.

This special event sheds insight on those who are incarcerated and on death row – exploring themes of friendship, compassion, and understanding the realities of a life behind bars. Proceeds from book sales and donations will support the Prison Library Project.