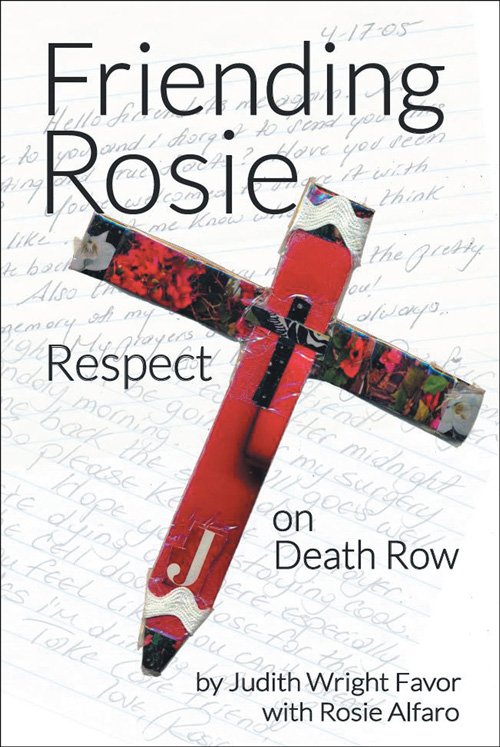

Friending Rosie: Page Publishing

Author

By Judith Favor

By Judith Favor

Trouble called me by name one Sunday afternoon at California Central

Women’s Facility. I had just finished co-leading a weekend Alternatives

to Violence Project workshop with three Quaker volunteers and had

walked with them from the cellblock to the exit gate. The moment I

passed through the Xray detector into the visitor’s room, the watch

sergeant called my name. His tone was stern. When I turned, an even

sterner voice added, “Miz Favor, I need to talk to you. In my office.” He

jerked a thumb over his shoulder.

Lieutenant and sergeant gave me hard looks as I stepped around the

end of the counter and followed them. Why did each man keep a hand

on the holstered pistols at his hip? Why address me with harsh eyes and

clipped voices? What was so threatening about a sixty-year-old

grandmother?

“What’s the problem, officer?”

“You broke the rules.”

“What rules?”

“Department of Corrections rules. You are prohibited from doing

volunteer work in the same prison where you visit an inmate.”

“I didn’t know there was a rule against that.”

“There is. We’re telling you. You cannot volunteer and also visit a Death

Row prisoner, or write to her. That is against the rules.”

“I’m trying see your point of view,” I began, thinking it wise to start off

diplomatically, “but I’ve been leading AVP workshops with the general

population for two years with no fuss. I know about the rule prohibiting

women on Death Row from participating in programs. Rosie is not

involved in the AVP program, so I don’t see the problem. Why can’t I

do both?”

The men shook their heads in unison. They folded arms across chests.

I tried another tack. “Getting to know Rosie was what inspired me to

train for AVP leadership. I want to show inmates how to solve

interpersonal problems nonviolently, because violence is what landed

Rosie behind bars.” More hard looks. I could tell they were not

persuaded.

“It is against department policy,” said the lieutenant.

“You can’t do both.”

I sensed it was fruitless to ask for an exception, but did it anyway.

“Could you grant me an exception to the rule? Everyone comes out

ahead when you give me permission to do both. Can you do that?”

Denied, of course. This conversation was not endearing me to the

lieutenant. I knew better than to insist on speaking to his supervisor, but

did it anyway. The sergeant punched a phone and summoned the watch

captain. Both guards kept arms crossed over their hearts. A stony

silence prevailed until the captain arrived. His furrowed brow showed

he was not happy to be here. I repeated my plea. He insistently repeated

the rule.

“No, you cannot do both.”

“But that’s not logical,” I protested. “Your policy doesn’t make sense in this situation.”

“NO,” repeated the captain. “Absolutely not!”

He gestured toward black binders labeled DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS.

“Prohibited. Period.”

“Well, you’re giving me a tough choice,” I said. “I’ll need some time to think about it.”

“No.” He gave me another hard look. “You can’t leave until you decide.”

I pictured my friends waiting in the parking lot. I met the captain’s stare. His jaw was set.

“Which is it? Decide now.” His eyes drilled into mine.

The pulse in my throat pounded so hard I thought my voice would shake,

but it came out steady and clear. ““Rosie. If I must choose now, I choose my friend Rosie.”

“Why?” The lieutenant sounded genuinely puzzled.

The other two exhaled noisily and shook their heads. One muttered something.

“Because she comes first for me. If you won’t let me facilitate workshops

here, other Quakers will do it. I can contribute at other California

prisons. Rosie is my friend. I will not abandon her.”

“Murderer.” The sergeant’s face twisted into a mocking sneer.

“You can all go.” The captain dismissed us and quickly left the room.

I felt discouraged as I drove away from Central California Women’s

Facility, where prison administrators and guards acted as if murderers

were monsters. They acted as if women on The Row could not be

redeemed. Their frozen faces seemed oblivious to my reasonable

questions, hardened against inquiry. Their scowling brows seemed

allergic to reflection. Their hard voices refused to consider any point of

view but Departmental Policy. Their hands on pistol butts conveyed

power and domination. The combination made mutual understanding

impossible. Compromise was totally off the table.

Soon after three armed men forced me to choose, I discovered “The

Abnormal Is Not Courage,” a poem by Jack Gilbert. His words about

World War II reminded me that Quaker volunteer service is not

accomplished with tanks or horses. Work for justice does not take place

on stallions, with sabers in hand. Witnessing to ‘the spark of God’ in

people occurs through everyday interactions. Sometimes it happens in

prisons, sometimes in homes, schools, retreat centers and cafes.

Sometimes it takes place in sunlight, usually in conversations that most

folks will never hear. Witnessing to “the spark of God” in myself, friends

behind bars (and you) comes through small moments of faithfulness and

simple actions that few will ever see. These days, for me, many faithful

actions take place on the pages of my forthcoming book titled

FRIENDING ROSIE: LIFE ON DEATH ROW.

At age seventy-nine, I lack the strength and energy to visit CCWF as

often as I once did, or as often as I would like, but my commitment to

Rosie remains steady and clear. My invitation to readers, to you, to hear,

see, correspond with and visit incarcerated persons is grounded in the

“normal excellence, of long accomplishment.” Twenty years after I first

ventured behind bars to meet Rosie, Gilbert’s poem reminds me that the

work of advocating for free people to befriend imprisoned ones is made

up of the “beauty of many days.”